With Roma, Alfonso Cuarón achieves what Terrence Malick only ever tried. The semi-autobiographical depiction of Cuarón's own childhood, narrated through the prism of a sublime cinematography, with a tone that tries to trigger some sort of transcendence in the spectator, immediately reminded me of The Tree of Life. However, Roma approaches the exercise very differently: with humility and simplicity. Contrary to its Texan counterpart, the Mexican chronicle doesn't feel awkward or weird at parts. It is complete, sound, and rich.

The children in the movies are only side characters. The main character is Cleo, the maid of the upper middle-class family, and nanny of the children. What makes the movie so peculiar is that it has an extremely non-didactic narration. As such, there is not much dialogs nor context about Cleo's life. She's a rather shy and silent young woman, and we can only try to read her state of mind from the numerous shots where she is pensively taking a break or just working in the house.

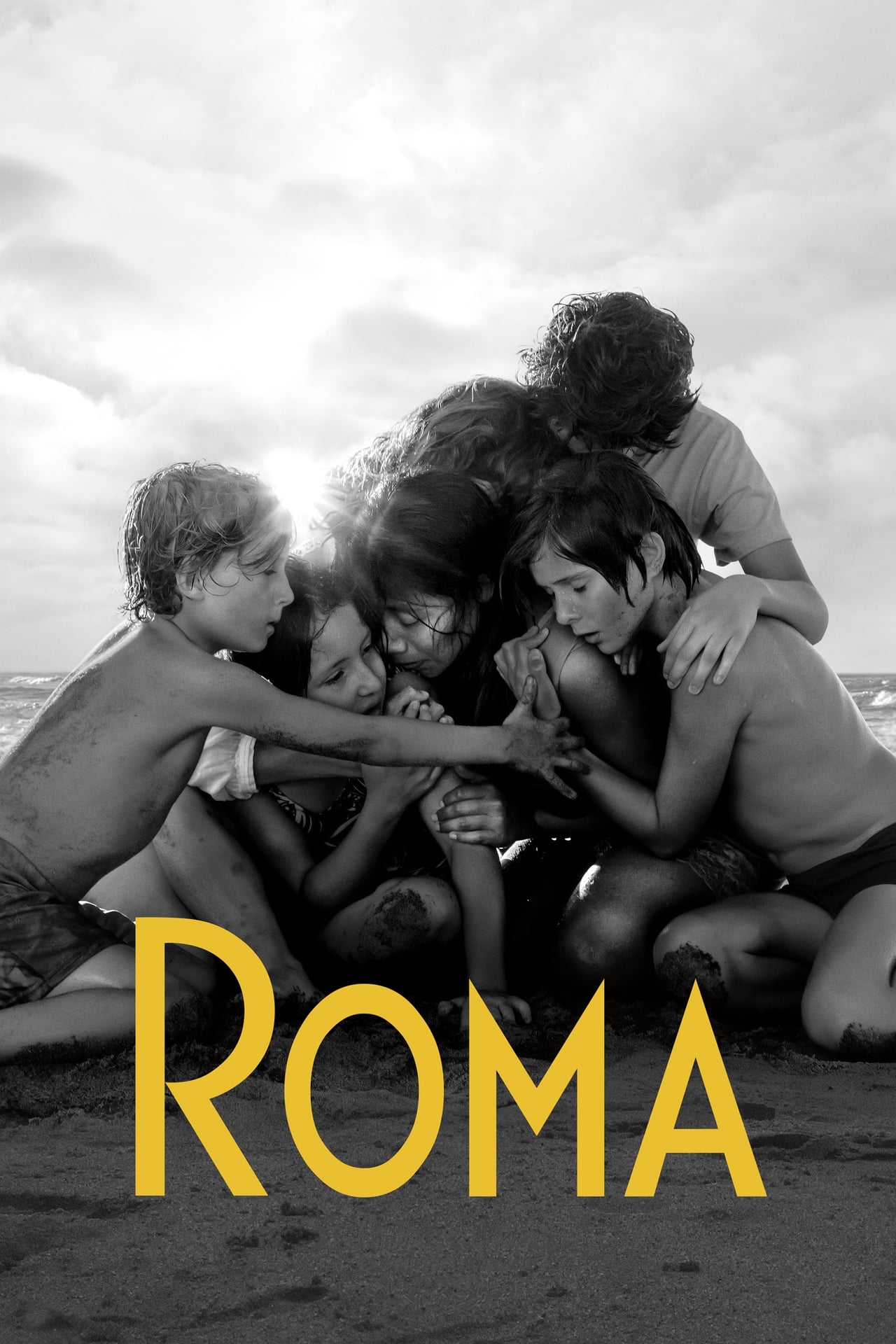

As far as we can tell, she is an angel. The archetype of the sweet, innocent, saintlike maid, is in fact so frankly painted that it seems Cuarón wasn't interested in drawing nuance, but rather in reporting his galvanized memories from childhood. In the movie, Cleo has a particularly loving relationship with the children, and the way the narration approaches her character matches the way the children must see her: a loving, pure, and protective angel.

The non-didactic narration goes on to include various elements of Mexico's culture without explaining them. There is a fanfare going on in the street of the house. Why? Is there some sort of celebration? There is a student's demonstration being repressed. Why? What are they protesting about? There is no explanation. The movie only shows, and never tell. I browsed quite a lot of interviews and Wikipedia articles afterwards, and I very much enjoy this procedure: first discover by the power of the image without understanding, and then, once the tale is over, go read about it.

Because the movie doesn't explain its context but only shows things happening, it holds an incredible richness. Since it doesn't explain, it doesn't have to summarize, and it doesn't have to simplify. It doesn't even have to take a side about anything. There is an incredible amount of detailed cultural and historical details that are left there for the spectator to care about and be curious about. And it works so well because those things happens in the movie like they would happen in life: you experience them without understanding all the implications.

The only thematic about which the story does take a stand is the place of women in society. Feminism isn't always found where we expect it, and as much as I think Spielberg's The Post was the most feminist movie of 2017, I think Roma is the most feminist of 2018. The movies draws an incredible, voluntarily non-subtle, harsh contrast between men and women: to all appearances men are strong and solid, while women are fragile and modest. But when it comes to reality, men are weak and cowards, while women are enduring all the pain, and are greatly brave. Cuarón said in an interview that Roma was a "love letter to the women who raised him". This is more than a love letter. This is an ode. The only representative of the male sex who are spared in the story are the children, who are still retaining the innocence of youngness. We can only hope that when they grow up they won't evolve into the kind of men who behaved so badly with the women raising them.

Roma needs to be experienced like a stroll. The first hour is slow, descriptive. It relaxed me. The second hour is way more turbulent, with drama and havoc as immersive as you can expect the craft of Alfonso Cuarón to be. The whole adventure followed me the days after, leaving a taste of peace and melancholy in my mind.

What is so good about this movie is that any action solely comes from the scene itself rather than from narrative tooling such as music or editing. The camera is either static or slowly moving, the shots are long, not aided by a piece of soundtrack. Yet the movie is intensively alive. It is so because of the many layers of stuff on the screen. The incredibly rich sets, the background noises of the neighborhood, the extras moving around in the background, the side characters doing their stuff to the side of the frame, and the profound, often silent, expressiveness of the main characters on the foreground. This whole beast of a movie is depicting life with a marvelous vividness, all that through a sequence of thoroughly designed frames.

Movie-making can sometimes feel like a sham in comparison to other arts. A 2-hours account of a story can hardly reach the intellectuel depth a book is able to contain, actors and their dialogs barely compete with the carefully crafted exchanges of theater plays, framing is just the successor of painting, and so on. But watching Roma is reassuring about the status of cinema, because you can't pull that shit up with anything else than a movie. It is cinema in its purest form, and an astounding achievement. One of the best film ever made.